The Critical Difference

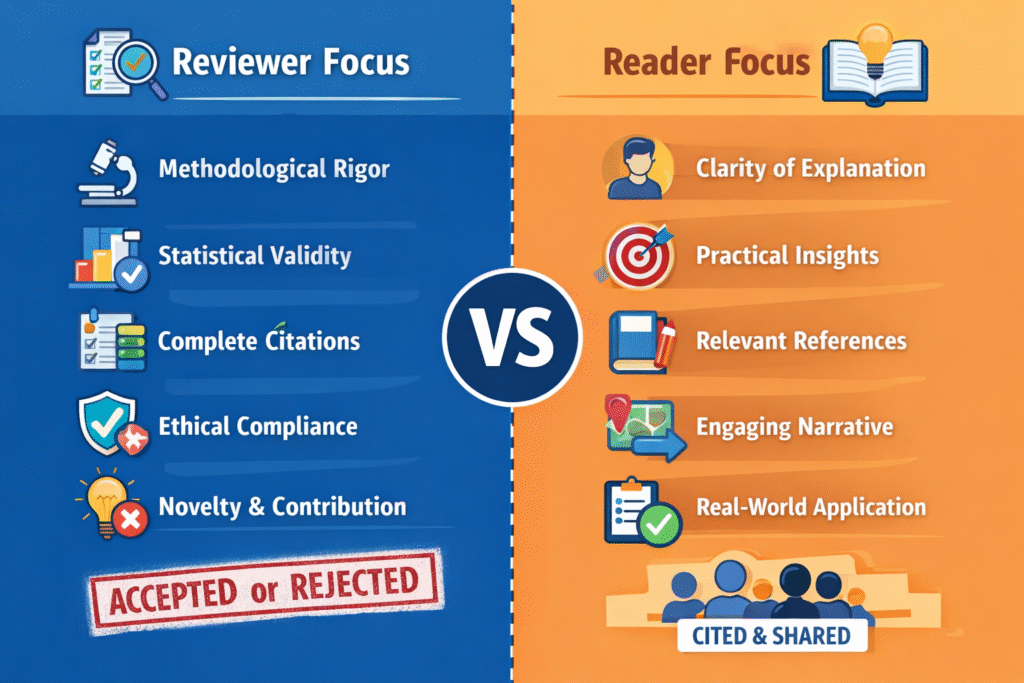

Most researchers think good academic writing means “clear language” and “strong data.” That’s only half the game. The real shift happens when you understand writing for reviewers vs readers — because they are not the same audience, not even close.

One group is judging whether your work deserves to exist in the scientific record. The other is trying to learn from it. If you write for only one, you risk losing both.

Let’s break down the difference of objective and subjective expectations and why it directly affects publication success, graduation writing assessment requirement outcomes, and long-term research impact.

Reviewers Read to Judge. Readers Read to Learn.

Peer reviewers approach your manuscript with a diagnostic mindset. Their job is to detect weaknesses, not admire strengths. They assess validity, methodology, novelty, and ethical compliance — the pillars of academic writing quality defined by global research standards such as international publication ethics bodies like the Committee on Publication Ethics.

Readers, on the other hand, are outcome-driven. They want clarity, usability, and takeaways. Clinicians look for application. Scholars look for insight. Students look for understanding. They are not scoring your methods section with a red pen.

Key point:

Reviewers read critically. Readers read practically.

If your paper only explains what you found without proving how rigorously you found it, reviewers will block it before readers ever see it.

The Objective vs Subjective Divide

This is where many manuscripts collapse.

| Dimension | Reviewers Care About (Objective) | Readers Care About (Subjective) |

| Data | Statistical validity, sample power | What do the numbers mean? |

| Citations | Completeness and credibility | Relevant to topic |

| Structure | Logical research flow | Easy to flow narrative |

| Method | Reproducibility, control, bias, reduction | Was the method reasonable? |

| Ethics | Consent, approvals, transparency | Usually assumed unlesss flagged |

| Novelty | Contribution beyond existing literature | Interesting or useful insight |

Reviewers operate in an objective evaluation framework, similar to formal graduation writing assessment requirement rubrics used in higher education institutions, where structured criteria determine pass or fail. Readers operate in a subjective comprehension framework — does this make sense, and does it help me?

You must satisfy both, but reviewers come first.

Why Most Rejections Happen at the Reviewer Level

Journals reject papers long before general readers ever engage. According to peer review models described in the Wikipedia overview of academic publishing, editorial decisions rely heavily on methodological soundness and contribution to the field, not writing style alone.

Common reviewer-triggered rejections include:

- Weak or poorly justified methodology

- Missing limitations

- Overstated conclusions

- Incomplete literature review

- Ethical transparency gaps

Notice something? None of these are about “interesting writing.” They are about research credibility.

This is why learning how to write a literature review that maps gaps, debates, and methodological precedents is not just academic tradition — it is reviewer survival strategy.

If your literature review reads like a summary instead of an argument, reviewers interpret that as intellectual immaturity.

Readers Care About Flow. Reviewers Care About Logic.

Readers appreciate narrative coherence. Reviewers demand structural logic.

Readers ask:

“Does this story make sense?”

Reviewers ask:

“Does this argument hold under scrutiny?”

That’s why structural tools matter. Even something as basic as organizing your work at a consistent writing desk workflow — outlining before drafting — directly improves reviewer readability by clarifying hypothesis progression and evidence placement.

Strong reviewer-focused structure usually looks like:

- Clear research question

- Justified study design

- Transparent methods

- Data aligned with objectives

- Limitations acknowledged before conclusions

Readers benefit from this too, but reviewers require it.

Style Alone Will Not Save Weak Science

Many authors assume polishing language is enough. It’s not.

Yes, readability matters. Yes, even famous figures like Helen Keller’s writing is celebrated for clarity and emotional power. But academic credibility is built on rigor, not eloquence.

Language editing improves reader engagement. Methodological precision secures reviewer approval.

That’s why professional academic editing services like those discussed in PaperEdit’s guide to research manuscript preparation emphasize structural review before language polishing. Editing cannot fix design flaws.

The Literature Review: Where Both Audiences Intersect

Your literature review is the only section where reviewer logic and reader curiosity meet.

Reviewers look for:

- Gap identification

- Theoretical grounding

- Methodological positioning

Readers look for:

- Context

- Why the topic matters

- What is already known

A strong review doesn’t just list studies. It builds a case. Resources such as structured academic guidance from platforms like PaperEdit’s academic writing resources highlight that literature reviews should function as arguments, not bibliographies.

This section often determines whether reviewers view you as a contributor or a novice.

Tone Differences: Precision vs Accessibility

Writing for reviewers demands precision:

- Avoid vague claims

- Quantify whenever possible

- Cite methodological precedents

- Declare limitations directly

Writing for readers demands accessibility:

- Define technical terms

- Explain implications

- Use clear transitions

- Highlight practical relevance

Balancing both methods is a skill taught in advanced academic writing programs and reinforced through editorial feedback systems like those described in one of our guides.

A paper that is precise but unreadable alienates readers. A paper that is readable but methodologically weak never passes review.

Ethical Transparency: A Reviewer Priority Readers Rarely Notice

Readers usually assume ethical compliance. Reviewers verify it.

Statements about:

- Ethics committee approval

- Participant consent

- Data transparency

- Conflict of interest

are essential because they align with international research integrity expectations, including standards promoted by organizations like the World Health Organizations.

If these elements are missing or unclear, reviewers interpret it as a red flag, even if the study findings are strong.

Writing Strategy: Sequence Matters

Here’s the smart order:

- Write for reviewers first

- Adjust for readers second

Start with rigor. Then refine readability.

This approach mirrors best practices shared in professional editorial training environments and structured support platforms such as PaperEdit’s manuscript readiness resources, where manuscripts are evaluated for both scientific strength and communication clarity.

Trying to impress readers before convincing reviewers is like designing a book cover before finishing the book.

Final Reality Check

If your goal is publication, graduation approval, or research credibility, you are writing in a system where reviewers are the gatekeepers.

Impress the reviewers with your manuscript by following our professionally tailored rules for academic writing.

Readers determine influence. Reviewers determine access.

Ignore either, and your research either never gets published or never gets read.

Mastering writing for reviewers vs readers means understanding that scientific communication is both a test and a conversation — and you have to pass the test before you join the conversation.